Sunday, March 17, 2013

The Mysterious Death of Actress Florence Deshon, 1

CHRONICLES OF CROTON’S BOHEMIA

Florence Hollywood

"All great love affairs end in tragedy."

So wrote Ernest Hemingway, a 19-year-old volunteer ambulance driver wounded in Italy and recuperating at a Red Cross hospital in Milan

Although she was passionately in love with him and they had planned to marry, Agnes later wrote to end their relationship. To assuage the hurt, Hemingway fictionalized the affair in his 1929 novel A Farewell to Arms, in which Catherine Barkley, the beautiful young nurse, dies.

A similar tragic love affair was played out on Croton's Mt. Airy America

Their story would make a great screenplay and film. It would open on a hot summer day in New York City America has not yet been drawn into the fierce war being waged in Europe . Eastman, separated from his wife, was heading down Madison Avenue. At 34th Street

In Max's own words, "She was by far the most beautiful thing I had ever seen." Impetuously, he turned and walked beside her on 34th Street

Cut now to Tammany Hall, the local Democratic Party’s headquarters, on East 14th Street Florence

The date is December 15, 1916. The occasion is the extravaganza known as the Masses Ball, modeled after the Beaux Arts Ball, the scandalous saturnalia inParis Greenwich Village institution popular with gawkers from uptown.

Admission is one dollar for those in costume and two dollars for those without. One account described it as “a procession of sheiks, cave-women, circus dancers, and the like, frequently showing for the times, generous amounts of flesh. For reasons of economy as well as titillation, hula skirts, ballet costumes, and ragged beggars’ garments were favored.”

John Fox, Jr., author of the bestselling 1908 novel The Trail of the Lonesome Pine, and a donor of $1,000 to The Masses, is among the attendees at the 1916 Masses Ball. He is accompanied by Florence Deshon, recently acclaimed by critics for her performance in the film Jaffery. The title role was played by imposingly tall British actor C. Aubrey Smith, who would be remembered for a succession of parts as stiff-upper-lipped British generals, businessmen and government officials.

Florence Deshon was no stranger to Broadway. Three years earlier, she had scored a hit singing and dancing in The Sunshine Girl, a musical comedy starring dancers Vernon

|

| Looking north up Broadway at 38th Street. The Knickerbocker Theatre is on the far right. The buildings on the left are the old Metropolitan Opera and the New York Times tower.

Born Florence Danks on July 19, 1893, in Tacoma, Washington, she took the stage name Deshon. With the emphasis on the last syllable, she thought it sounded French. When her British father, a Linotype operator, deserted the family, Florence quit high school to support her Hungarian mother, Caroline.

Max Eastman immediately spotted

Eastman later captured the excitement of their first meeting. He recalled: "We talked fervently as we danced, and our minds flowed together like two streams from the same source rejoining. She was 21, and in exactly that state of obstreperous revolt against artificial limitations which I had expressed in my junior and senior essays in college."

“What do I care about a flag?”

She lived with her mother in a two-room apartment at

Florence Deshon

During dinner she expressed her scorn for men's attitudes toward women. "You can't do any little thing to please your own taste in this town without starting a riot," she told him. "I once got a present of a little Japanese silk parasol. It was becoming to me, and I thought it would be fun to carry it. Do you know I never got any farther than

Max described how they made love in the Croton house, a former cider mill. "We slept side-by-side in the corner bed by the big moonlit window, a very tranquil tenderness filling our hearts." (The former Max Eastman house at the head of

Meshing the lives and careers of two creative personalities was not easy. Max was traveling around the country speaking against war and for women’s suffrage.

She and her mother moved to a small apartment on

Max was so taken by

Their love affair continued, but

|

Saturday, March 16, 2013

Florence Deshon, 2: Charlie Chaplin or Max?

CHRONICLES OF CROTON’S BOHEMIA

Florence was kept busy early in 1918 making eight films at the Vitagraph Studios in the Midwood section of Brooklyn . Her career went into what Eastman described as "a dead calm” later that year.Florence accompanied him on one of his visits to the Chaplin studio. Chaplin greeted them warmly. The trio soon became frequent companions, playing charades and other games at parties. Chaplin was obviously entranced by Florence 's quick mind and radiant beauty.

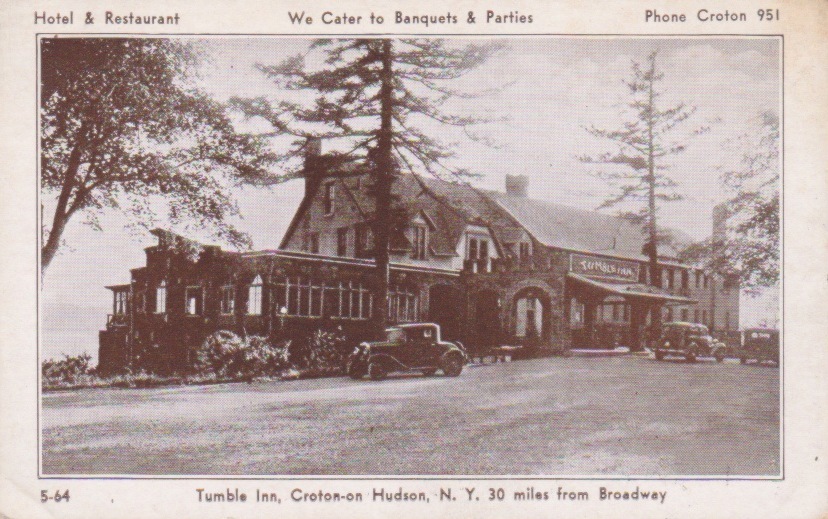

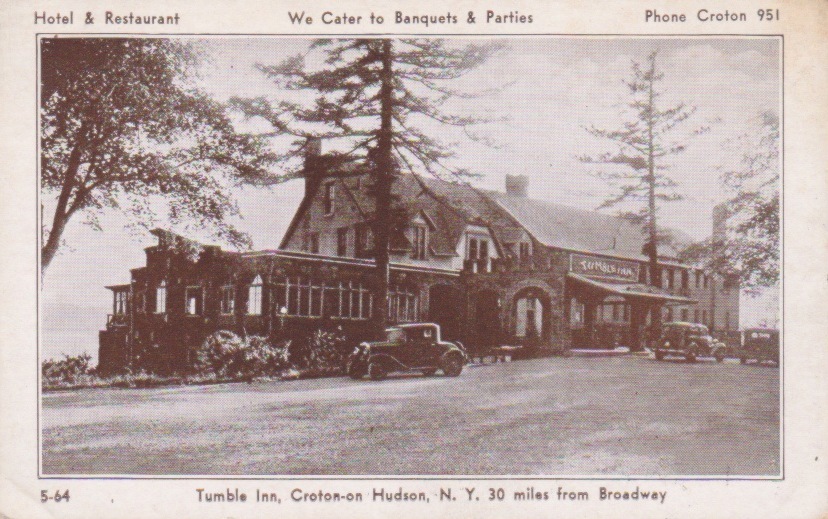

Florence ’s letters to him told of her film work and began mentioning Chaplin frequently: "Charlie is always sweet to me," one letter said. "I dined with Charlie on Christmas Eve, and he gave me a Christmas present," another reported.Florence underwent an operation that afternoon and spent the next days convalescing at the house in Croton. When she felt better, she took the train to New York to be with Chaplin, who had traveled east with her. This was a period when Florence --in Eastman's own words--"commuted between two lovers." Chaplin came up to Croton and took a room for a few days at the Tumble Inn, a roadhouse on the

Chaplin came up to Croton and took a room for a few days at the Tumble Inn, a roadhouse on the Albany Post Road . (The Tumble Inn was demolished in 1974. The Skyview Nursing Home now occupies the site.)

Florence and Charlie spent many hours there and walked the roads of Croton together. She could not persuade him to accompany her to Max's Mt. Airy

The love affair between Max Eastman and Florence Deshon would set the pattern for his later romances.

Initially, he was completely head-over-heels in love. The time they spent together--stolen from two blossoming careers--was a storybook romance.

Max, an inveterate philanderer, wrote: "For the first time in my life I experienced no carnal or romantic yearning toward the shapely breasts and delicately upward curving calves of the summer-clad girls who would pass me on the street. Night and day I was absorbed in my greatest love. I was, in fact and to my amazement, monogamous.

"Indeed I was so completely lifted into heaven by Florence 's body and spirit, that I feared for my own terrestrial selfhood, for my ambitions. Together with this fear of losing myself, I began also to experience a fear of losing her. I thought I saw evidences that she was drifting away from me."

|

Movie stars sent "signed" photo cards like this to fans in the 1920s. This is Florence Deshon's card from the Billy Rose Theatre Collection at the New York Public Library.

|

In June, they moved into his Croton house for the summer, and she seemed to him almost like a wife. "The exhilaration and the tender joy of our days together," Max recorded, "our walks through the wakening wood, or over the hill roads to the great dam, and in the midst of those days the sudden thought, quickening my pulse, that the nights also were mine, made me believe in love in a way that I would once have called old-fashioned.

"The present was thrilling, the future was full of adventures for us both: 'Till death do us part,' if those words had been spoken, would not have been discordant during the early summer of 1918."

Despite these emotions, trouble was brewing in paradise. Once while Max was busy writing in the Croton house, Florence began preparing lunch. At an impasse in the piece, he left his desk to walk on Mt. Airy Road and sort out his thoughts. When he returned a short time later, he found her standing in the doorway in a black rage. She had turned off the stove, leaving the food half-cooked.

"What do you think I am, a servant?" she snapped. "Do you think I came up here to cook for you while you stroll around the countryside?" The storm soon blew over, and the couple made peace.

As loose as his ties to Florence were, one morning in late August Max was seized by a wish to be free of commitment. For no apparent reason, he abruptly lost interest. The relationship that seemed so idyllic only a few weeks before, suddenly became confining. In 1912, the same feeling had come over him toward his wife, Ida Rauh, to whom he was still married.

Max kept up a semblance of romantic love, but Florence must have sensed the change in his feelings. In July of 1919, when a contract offer came from Samuel Goldwyn in California she quickly signed with him and began work on a new film in August. In September, Max joined her there.

The reunited lovers found an apartment in Hollywood , where Max could continue to work on his book on the sense of humor. Once they settled into it, Max called on Charlie Chaplin. Eastman and Chaplin had met the previous winter after Max had spoken in Seattle in support of striking shipyard workers. They became fast friends, finding their political attitudes and intellectual (and sexual) interests compatible.

|

| Charlie Chaplin welcomes Max Eastman to Hollywood. |

Max returned to New York by way of San Francisco , where he looked up a young woman whose poems he had published in The Liberator, the successor magazine to The Masses. They ended up going to bed together, but his conscience was only slightly troubled. After all, he and Florence had an agreement about mutual independence.

Chaplin would go to Florence 's apartment following his work at the studio and spend the evening with her. Before long, he was spending the night, as well. Hollywood gossips began talking about the comedian's romance with Florence .

She made three films for Goldwyn: The Loves of Letty, Duds, and Dollars and Sense, and two (Dangerous Days and The Cup of Fury) for Eminent Authors Pictures, a company formed by Goldwyn with novelist Rex Beach and other authors. After completing the fifth film, Florence was kept idle by the studio. Finally, Goldwyn told her that he wanted to break her contract, offering a thousand dollars and a ticket back to New York .

Three studios immediately made offers at double her Goldwyn salary. After making a Western for Fox titled The Twins of Suffering Creek, she joyfully telegraphed Max that she had agreed to work for veteran director Maurice Tourneur for $350 a week "in a big part." The film was Deep Waters. She would be playing opposite the male lead, Jack Gilbert, who would later become better known as silent film idol John Gilbert.

In the meantime, back in New York Max was far from sexually abstinent. He had become captivated by Lisa Duncan, one of the six foster daughters of Irma Duncan, herself a pupil of Isadora. Irma Duncan had begun adoption proceedings to facilitate their entrance to the United States in 1914, but actual adoption never took place.

Instead of answering Florence 's elated telegram with congratulations, Max sent her a letter declaring his love for Lisa. The cruelest blow was his account of watching her dance in Carnegie Hall: "I was entranced way beyond any thought by the perfection of her being."

In the summer of 1920, Florence reported to Max that she was not feeling well, and he convinced her to join him in Croton. She arrived on August 20, obviously unwell. He immediately made an appointment with his friend, Dr. Herman “Harry” Lorber, who treated most of Greenwich Village 's artists and intellectuals.

"You came just in time," Lorber told him, after examining Florence . "Only an immediate operation can save her from a blood-poisoning that might be fatal. I wonder what kind of a doctor she had out there [in Los Angeles ]."

Eastman did not seem to understand. Lorber made his diagnosis specific: "Florence has been pregnant for three months, and the fetus is dead. I don't know how long ago it died, but any delay might be fatal." Max realized that the child she was carrying had to have been fathered by Chaplin, whose predatory sexual appetite and habit of not taking precautions were well-known around Hollywood .

Neither Eastman or Chaplin exhibited any jealousy. "There was something royal in her nature that gave her the right to have things as she pleased," Max later wrote.

When the time came for her to decide whether to go back to California with Chaplin, she chose to remain in Croton with Max. Chaplin accompanied her to Grand Central Terminal, where they parted at the gate to the Croton train. "Don't mind these tears," he told her. "I'll be all right."

Friday, March 15, 2013

Florence Deshon, 3: Suicide or Accident?

CHRONICLES OF CROTON’S BOHEMIA

Florence returned to Hollywood Hollywood Florence New York

Florence California

Together again in Croton, Florence Deshon and Max Eastman clashed frequently. Florence

|

| .Movies were purveyors of images of unattainable goddesses and gods. This is Florence Deshon in 1916 |

After completing the manuscript of his book on the sense of humor, Max returned to New York Florence

In the autumn of 1921, Florence returned to New York Europe .

A militant suffragist, Stevens had shared a house in Croton with Malone, an attorney who had resigned as Collector of the Port of New York, a political plum of a job, to protest the rough treatment given to women picketing the White House.

|

| Florence Deshon's subleased apartment was in Rhinelander Gardens on West 11th Street. Photographed by Berenice Abbott in 1937.

The Stevens apartment was in

Located on the south side of

|

|

| Detail of the cast iron balconies at Rhinelander Gardens as photographed by Berenice Abbott in 1937.

According to Max, Friday night, February 4, 1922, he was attending a Broadway play with artist Neysa McMein when a man tapped him on the shoulder and whispered, "Florence Deshon has been taken to the hospital. She turned on the gas in her room. She's in

Earlier that day, Max had met Max rushed to the hospital and was told that Eastman later recounted the story of their flawed romance and A news story in The New York Times for Saturday, February 5, 1922, reported that Ms. Minnie Morris, described as a newspaperwoman, had returned to her apartment Friday night and detected the odor of gas. She found A follow-up story in the Times on Sunday, February 6, reported, "None of the friends of Florence Deshon, film actress, friend of Charlie Chaplin and of Max Eastman, could find the least motive yesterday in her death. All declared the gas must have been turned on accidentally, and the Medical Examiner has reached the same conclusion." Funeral services for her were held at noon Monday, February 7, at Frank E. Campbell's Rumors persisted, however, that she had killed herself over personal problems. Some even suggested that she had quarreled with Max. One neighbor told about a dispute that had taken place in When a Times reporter contacted him, Max strongly denied the charge: "It is absolutely false. Miss Deshon was a dear friend of mine, and I am sure her death was accidental. There was no reason in the world why she should take her life, and no letter has been found or received to indicate that she did. She was healthy and happy when I saw her, on Thursday afternoon [not Friday afternoon, as his book has it], and we had an engagement for the theatre on Saturday. Please do not question me any more about it." The Sunday Times story reported that Max had gone to the hospital on Saturday morning [not Friday night], when doctors made a final attempt to revive her, and a blood transfusion was performed. It concluded with the news that at the time of her death the offer of a part in a play was awaiting her acceptance. Not long after the funeral, Eastman left on a planned trip to an international conference in He was trailed by many questions: Was Florence Deshon's death an accident? A suicide? How to account for the open window in February? Had the flame been lit and blown out by a draft of air? Why would the gas have been lit when electric illumination was available? And how to explain the absence of a farewell note from a young woman who regularly poured out her soul in letters to friends? The past guards its secrets well, and the big question remains unanswered: What were the true circumstances behind Florence Deshon's death? |

Epilogue

In 1955, the eight row houses of Rhinelander Gardens

For years accounts of Florence Deshon’s career and death have maintained that her grave site was unknown. Cemetery records were scoured in her birthplace, Tacoma, Washington, and Hollywood, California, to no avail. Nor was she buried in the Actors Fund plot in Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, N.Y. or in the earlier Actors Fund plot in the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Diligent research, however, has solved this mystery. It turns out that Florence Deshon was quietly buried inNew York Mt. Zion Cemetery in Maspeth in the borough of Queens , along what is designated as Path 10 in the Left Section of the cemetery.

Diligent research, however, has solved this mystery. It turns out that Florence Deshon was quietly buried in

Beautiful Florence Deshon was only 28 years old when she died mysteriously. She joined two other creative artists associated with Broadway and Hollywood who also died young and are buried in Mt. Zion Cemetery