Tuesday, May 21, 2013

The Demeaning of Memorial Day

OP ED

Waterloo 's flags were

lowered to half-staff, and draped with evergreen sprays and black mourning

ribbons on May 5, 1866. Local civic societies and residents marched to the

village's three cemeteries, where ceremonies were held and the graves were decorated.

In 1868, Waterloo

joined other communities in holding their Decoration Day observance on May 30,

as the GAR's General Logan had urged.

This

year Memorial Day will be celebrated on Monday, May 27. With its roots deep in

the Civil War, for more than a century this solemn holiday was traditionally

observed on May 30. Ever since 1971, however, in a concession to expediency and

a rebuke to tradition, Congress shifted Memorial Day to the last Monday in May.

Thanks to the Uniform Holidays Act, the holiday can now fall on any of the

eight days between May 24 and May 31.

On this coming Monday, May 27 at Arlington National Cemetery Fredericksburg Confederate Cemetery

Its

origins virtually forgotten, for many Americans Memorial Day is no longer a day

of remembrance. Instead, it’s just another three-day weekend holiday--an

occasion for barbecues, picnics and shopping mall sales. Regrettably, the number of communities that

celebrate the holiday in the old-fashioned way with colorful parades grows

smaller each year, especially among cities and larger communities. Manhattan ’s time-honored parade up Fifth Avenue Long Island .

In Westchester ,

the parade tradition is also still strong. Parades were held last year in

Ardsley, Bedford Hills, Bronxville,

Dobbs Ferry, Eastchester, Elmsford, Harrison, Irvington ,

Mount Kisco ,

New Castle , New Rochelle ,

Pelham, Pleasantville, Scarsdale , Tarrytown, White Plains , and the Crestwood and Ferncliff Manor

sections of Yonkers

Lest We Forget

Some

620,000 soldiers died in the Civil War, 60 percent of them on the Union side and

40 percent on the Confederate side, making it the bloodiest event in U.S.

history, and exceeding by more than 50 percent the military deaths in World War

II.

Until

the Korean War, the death toll of the Civil War nearly equaled the total number

killed in all previous U.S.

wars. If the same percentage of Americans had died in the Vietnam War as died

in the Civil War, four million names would be on the somber black wall of Vietnam

Memorial in Washington .

By

the Civil War’s end, hardly an American family had not been touched by its

appalling death toll. About 6 percent of white males of military age in the

North and about 18 percent of their southern counterparts died in the war.

Virulent infectious diseases--typhoid fever, dysentery and pneumonia--killed more

than twice the number of battle deaths.

Death

on such a grand scale cried out for meaning and emotional justification. Well

before the Civil War ended, women on both sides had begun rituals of

remembrance with processions to local cemeteries to decorate the graves of

Civil War veterans. Thus was born the national holiday of Decoration Day that

would later be called Memorial Day.

In 1866, veterans who had

served in the Union Army formed an organization called the Grand Army of the

Republic (GAR). The following year, Gen. John A. "Black Jack" Logan was elected its

national commander.

With a membership approaching a

half-million, for many years to come the GAR would be a major national

political force. Its final encampment was held on August 31, 1949, with six of

the 19 living Union Army veterans in attendance. The GAR disbanded in 1956,

after the death of Albert Woolson, the last surviving veteran, at age 107.

On May 5,

1868, General Logan proclaimed Decoration Day as a holiday and set the first

official observance for May 30, closing his General Oder No. 11 to the GAR

"with the hope that it will be kept up from year to year."

Celebrated for the first time on May 30 of 1868, the date was chosen because it

was not the anniversary of a

specific battle.

Some two dozen communities have

since claimed to be the birthplace of the holiday. Evidence also supports the

claim that Southern women were decorating graves of their war dead even before

the end of hostilities.

How the Holiday Began

On April

25, 1866, in Columbus , Mississippi ,

a group of women visited a cemetery to place flowers on the grave of

Confederate soldiers killed at the battle of Shiloh .

Nearby were the graves of Union soldiers. Concerned over the bare gravesites,

the women also placed flowers on their graves.

Additional

claimants include Macon and Columbus in Georgia ,

and Carbondale , Illinois Carbondale

was the wartime home of General Logan.

In 1966,

after much research, the Erie Canal village

of Waterloo

On May

26, 1966, just in time for that year's celebration, President Lyndon B. Johnson

signed a presidential proclamation recognizing Waterloo as the birthplace of the holiday.

In the

summer of 1865, Henry C. Welles, a Waterloo

druggist, suggested that the Civil War dead in local cemeteries should be

remembered by placing flowers on their graves. Nothing came of this until the

following spring, when he brought his idea to Seneca County

Despite New York ’s claim, the

tiny central-Pennsylvania hamlet of Boalsburg insists the custom of honoring

Civil War dead began there in 1864, while the Civil War still raged. On a

pleasant October Sunday that year, a teenage girl named Emma Hunter brought

flowers to the Zion

Lutheran Church

Nearby,

Elizabeth Meyer was placing flowers on the grave of her son, Pvt. Amos Meyer,

who had died on the final day of battle at Gettysburg . Emma put a few of her flowers on

Amos’s grave. In turn, Mrs. Meyer placed some of her flowers on Dr. Hunter’s

grave.

United by

loss, the two women agreed to meet the next year on the Fourth of July to

repeat the ceremony and also to place flowers on undecorated graves. On that

date, they were joined by other residents. Dr. George Hall, a local clergyman,

offered a prayer, and every grave in the cemetery was decorated with flags and

flowers. The custom became an annual event, soon copied by neighboring

communities.

. In the

beginning, the South refused to recognize the May 30 federal holiday, and

honored Confederate dead on other dates, including the birthdays of Gen. Robert

E. Lee, January 29, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis, June 3. Michigan made Decoration

Day an official state holiday in 1871. By 1890, every other northern state had

done the same.

The Holiday Today

Memorial Day, the alternative name of the

holiday, was first used in 1882, but did not displace Decoration Day until

after World War II. It became the official name of the holiday in 1967.

The following year, Congress made

wholesale changes in four holidays to take effect at the federal level in 1971.

In addition to shifting Memorial Day from May 30 to the last Monday in May,

Washington's Birthday was moved from February 22 to the third Monday in

February (and celebrated as Presidents Day), and Columbus Day was changed from

October 12 to the second Monday in October.

Formerly called Armistice Day, Veterans Day

was also shifted from November 11 (the

date hostilities of World War I ended in 1918) to the fourth Monday of

October. Congress moved this

holiday back to November 11 in 1978 because too many other nations continued to

celebrate the original date.

The late Sen.

Daniel K. Inouye (D-Hawaii), a Medal of Honor recipient who lost an arm

fighting in Italy

during World War II, introduced a bill in the Senate in 1999 to restore the

Memorial Day holiday to its original date, May 30. His bill and subsequent

bills introduced by him at each session of Congress until his death in 2012 were

allowed to die in committee.

Sadly, Memorial Day in America

Sunday, March 17, 2013

The Mysterious Death of Actress Florence Deshon, 1

CHRONICLES OF CROTON’S BOHEMIA

Florence Hollywood

"All great love affairs end in tragedy."

So wrote Ernest Hemingway, a 19-year-old volunteer ambulance driver wounded in Italy and recuperating at a Red Cross hospital in Milan

Although she was passionately in love with him and they had planned to marry, Agnes later wrote to end their relationship. To assuage the hurt, Hemingway fictionalized the affair in his 1929 novel A Farewell to Arms, in which Catherine Barkley, the beautiful young nurse, dies.

A similar tragic love affair was played out on Croton's Mt. Airy America

Their story would make a great screenplay and film. It would open on a hot summer day in New York City America has not yet been drawn into the fierce war being waged in Europe . Eastman, separated from his wife, was heading down Madison Avenue. At 34th Street

In Max's own words, "She was by far the most beautiful thing I had ever seen." Impetuously, he turned and walked beside her on 34th Street

Cut now to Tammany Hall, the local Democratic Party’s headquarters, on East 14th Street Florence

The date is December 15, 1916. The occasion is the extravaganza known as the Masses Ball, modeled after the Beaux Arts Ball, the scandalous saturnalia inParis Greenwich Village institution popular with gawkers from uptown.

Admission is one dollar for those in costume and two dollars for those without. One account described it as “a procession of sheiks, cave-women, circus dancers, and the like, frequently showing for the times, generous amounts of flesh. For reasons of economy as well as titillation, hula skirts, ballet costumes, and ragged beggars’ garments were favored.”

John Fox, Jr., author of the bestselling 1908 novel The Trail of the Lonesome Pine, and a donor of $1,000 to The Masses, is among the attendees at the 1916 Masses Ball. He is accompanied by Florence Deshon, recently acclaimed by critics for her performance in the film Jaffery. The title role was played by imposingly tall British actor C. Aubrey Smith, who would be remembered for a succession of parts as stiff-upper-lipped British generals, businessmen and government officials.

Florence Deshon was no stranger to Broadway. Three years earlier, she had scored a hit singing and dancing in The Sunshine Girl, a musical comedy starring dancers Vernon

|

| Looking north up Broadway at 38th Street. The Knickerbocker Theatre is on the far right. The buildings on the left are the old Metropolitan Opera and the New York Times tower.

Born Florence Danks on July 19, 1893, in Tacoma, Washington, she took the stage name Deshon. With the emphasis on the last syllable, she thought it sounded French. When her British father, a Linotype operator, deserted the family, Florence quit high school to support her Hungarian mother, Caroline.

Max Eastman immediately spotted

Eastman later captured the excitement of their first meeting. He recalled: "We talked fervently as we danced, and our minds flowed together like two streams from the same source rejoining. She was 21, and in exactly that state of obstreperous revolt against artificial limitations which I had expressed in my junior and senior essays in college."

“What do I care about a flag?”

She lived with her mother in a two-room apartment at

Florence Deshon

During dinner she expressed her scorn for men's attitudes toward women. "You can't do any little thing to please your own taste in this town without starting a riot," she told him. "I once got a present of a little Japanese silk parasol. It was becoming to me, and I thought it would be fun to carry it. Do you know I never got any farther than

Max described how they made love in the Croton house, a former cider mill. "We slept side-by-side in the corner bed by the big moonlit window, a very tranquil tenderness filling our hearts." (The former Max Eastman house at the head of

Meshing the lives and careers of two creative personalities was not easy. Max was traveling around the country speaking against war and for women’s suffrage.

She and her mother moved to a small apartment on

Max was so taken by

Their love affair continued, but

|

Saturday, March 16, 2013

Florence Deshon, 2: Charlie Chaplin or Max?

CHRONICLES OF CROTON’S BOHEMIA

Florence was kept busy early in 1918 making eight films at the Vitagraph Studios in the Midwood section of Brooklyn . Her career went into what Eastman described as "a dead calm” later that year.Florence accompanied him on one of his visits to the Chaplin studio. Chaplin greeted them warmly. The trio soon became frequent companions, playing charades and other games at parties. Chaplin was obviously entranced by Florence 's quick mind and radiant beauty.

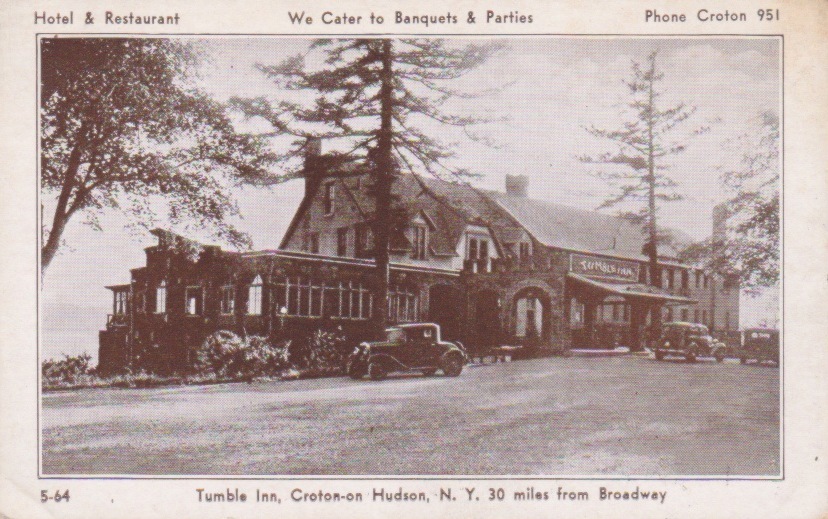

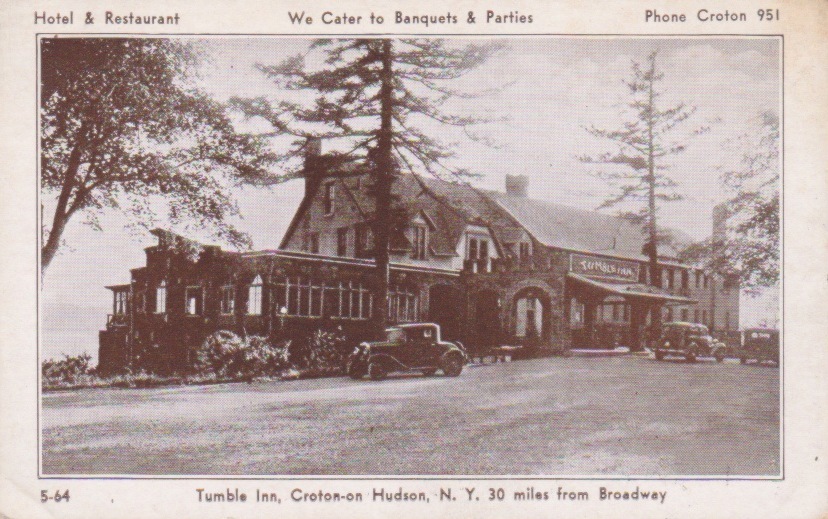

Florence ’s letters to him told of her film work and began mentioning Chaplin frequently: "Charlie is always sweet to me," one letter said. "I dined with Charlie on Christmas Eve, and he gave me a Christmas present," another reported.Florence underwent an operation that afternoon and spent the next days convalescing at the house in Croton. When she felt better, she took the train to New York to be with Chaplin, who had traveled east with her. This was a period when Florence --in Eastman's own words--"commuted between two lovers." Chaplin came up to Croton and took a room for a few days at the Tumble Inn, a roadhouse on the

Chaplin came up to Croton and took a room for a few days at the Tumble Inn, a roadhouse on the Albany Post Road . (The Tumble Inn was demolished in 1974. The Skyview Nursing Home now occupies the site.)

Florence and Charlie spent many hours there and walked the roads of Croton together. She could not persuade him to accompany her to Max's Mt. Airy

The love affair between Max Eastman and Florence Deshon would set the pattern for his later romances.

Initially, he was completely head-over-heels in love. The time they spent together--stolen from two blossoming careers--was a storybook romance.

Max, an inveterate philanderer, wrote: "For the first time in my life I experienced no carnal or romantic yearning toward the shapely breasts and delicately upward curving calves of the summer-clad girls who would pass me on the street. Night and day I was absorbed in my greatest love. I was, in fact and to my amazement, monogamous.

"Indeed I was so completely lifted into heaven by Florence 's body and spirit, that I feared for my own terrestrial selfhood, for my ambitions. Together with this fear of losing myself, I began also to experience a fear of losing her. I thought I saw evidences that she was drifting away from me."

|

Movie stars sent "signed" photo cards like this to fans in the 1920s. This is Florence Deshon's card from the Billy Rose Theatre Collection at the New York Public Library.

|

In June, they moved into his Croton house for the summer, and she seemed to him almost like a wife. "The exhilaration and the tender joy of our days together," Max recorded, "our walks through the wakening wood, or over the hill roads to the great dam, and in the midst of those days the sudden thought, quickening my pulse, that the nights also were mine, made me believe in love in a way that I would once have called old-fashioned.

"The present was thrilling, the future was full of adventures for us both: 'Till death do us part,' if those words had been spoken, would not have been discordant during the early summer of 1918."

Despite these emotions, trouble was brewing in paradise. Once while Max was busy writing in the Croton house, Florence began preparing lunch. At an impasse in the piece, he left his desk to walk on Mt. Airy Road and sort out his thoughts. When he returned a short time later, he found her standing in the doorway in a black rage. She had turned off the stove, leaving the food half-cooked.

"What do you think I am, a servant?" she snapped. "Do you think I came up here to cook for you while you stroll around the countryside?" The storm soon blew over, and the couple made peace.

As loose as his ties to Florence were, one morning in late August Max was seized by a wish to be free of commitment. For no apparent reason, he abruptly lost interest. The relationship that seemed so idyllic only a few weeks before, suddenly became confining. In 1912, the same feeling had come over him toward his wife, Ida Rauh, to whom he was still married.

Max kept up a semblance of romantic love, but Florence must have sensed the change in his feelings. In July of 1919, when a contract offer came from Samuel Goldwyn in California she quickly signed with him and began work on a new film in August. In September, Max joined her there.

The reunited lovers found an apartment in Hollywood , where Max could continue to work on his book on the sense of humor. Once they settled into it, Max called on Charlie Chaplin. Eastman and Chaplin had met the previous winter after Max had spoken in Seattle in support of striking shipyard workers. They became fast friends, finding their political attitudes and intellectual (and sexual) interests compatible.

|

| Charlie Chaplin welcomes Max Eastman to Hollywood. |

Max returned to New York by way of San Francisco , where he looked up a young woman whose poems he had published in The Liberator, the successor magazine to The Masses. They ended up going to bed together, but his conscience was only slightly troubled. After all, he and Florence had an agreement about mutual independence.

Chaplin would go to Florence 's apartment following his work at the studio and spend the evening with her. Before long, he was spending the night, as well. Hollywood gossips began talking about the comedian's romance with Florence .

She made three films for Goldwyn: The Loves of Letty, Duds, and Dollars and Sense, and two (Dangerous Days and The Cup of Fury) for Eminent Authors Pictures, a company formed by Goldwyn with novelist Rex Beach and other authors. After completing the fifth film, Florence was kept idle by the studio. Finally, Goldwyn told her that he wanted to break her contract, offering a thousand dollars and a ticket back to New York .

Three studios immediately made offers at double her Goldwyn salary. After making a Western for Fox titled The Twins of Suffering Creek, she joyfully telegraphed Max that she had agreed to work for veteran director Maurice Tourneur for $350 a week "in a big part." The film was Deep Waters. She would be playing opposite the male lead, Jack Gilbert, who would later become better known as silent film idol John Gilbert.

In the meantime, back in New York Max was far from sexually abstinent. He had become captivated by Lisa Duncan, one of the six foster daughters of Irma Duncan, herself a pupil of Isadora. Irma Duncan had begun adoption proceedings to facilitate their entrance to the United States in 1914, but actual adoption never took place.

Instead of answering Florence 's elated telegram with congratulations, Max sent her a letter declaring his love for Lisa. The cruelest blow was his account of watching her dance in Carnegie Hall: "I was entranced way beyond any thought by the perfection of her being."

In the summer of 1920, Florence reported to Max that she was not feeling well, and he convinced her to join him in Croton. She arrived on August 20, obviously unwell. He immediately made an appointment with his friend, Dr. Herman “Harry” Lorber, who treated most of Greenwich Village 's artists and intellectuals.

"You came just in time," Lorber told him, after examining Florence . "Only an immediate operation can save her from a blood-poisoning that might be fatal. I wonder what kind of a doctor she had out there [in Los Angeles ]."

Eastman did not seem to understand. Lorber made his diagnosis specific: "Florence has been pregnant for three months, and the fetus is dead. I don't know how long ago it died, but any delay might be fatal." Max realized that the child she was carrying had to have been fathered by Chaplin, whose predatory sexual appetite and habit of not taking precautions were well-known around Hollywood .

Neither Eastman or Chaplin exhibited any jealousy. "There was something royal in her nature that gave her the right to have things as she pleased," Max later wrote.

When the time came for her to decide whether to go back to California with Chaplin, she chose to remain in Croton with Max. Chaplin accompanied her to Grand Central Terminal, where they parted at the gate to the Croton train. "Don't mind these tears," he told her. "I'll be all right."